Sometimes these reports unearth big surprises, as has just happened in number 5 Calle Archivos. There is no doubt that it was an important house, not only because of its size, but also because the main facade of the building overlooks the Plaza Mayor in the heart of the town.

The Technicians from Villajoyosa Historical Heritage are used to making ‘pre authorisation of works’ studies in lots of old houses but, from the moment they set foot in the hallway they became aware that this was different. The first two floors were almost identical, with large kitchens, a small room with a look out window over the main entrance. The hallway had a staircase giving access to a passage on the mezzanine floor, closed by a full size metal barred gate decorated with religious symbols that today could easily go unnoticed by the majority of people. Whilst carrying out such reports, this is the kind of detail which is analysed as it could hold the key to understanding who lived there, what they did, what interests/hobbies they had...

On the gate, nearly all the bars are painted in grey, they immediately noticed a large chalice and high up were two pomegranates. The interior style of the house speaks to us of an important alteration in the 19th century. The society of that century was mainly religious. However, that doesn’t explain a priestly symbol such as a chalice and another symbol so special and so unusual as a pomegranate, which represents the Virgin Mary. Little by little other symbols appeared such as the ‘rosácea’ a rosette with six petals, a pre-Roman religious symbol that we frequently find in the Celtic world. Also, the Church used the symbol in the stained glass rose windows in Roman and Gothic churches to allow light to flood in. In the Christian religion it means exactly that – the light of Christ as the centre of everything, as the only truth. This symbol appears at least four times in the house: in the studded decoration of the metallic plate on the door (which is going to be recovered as part of the alteration work), on a ventilation aperture in a room and at least in two pieces of graffiti inscribed in separate rooms.

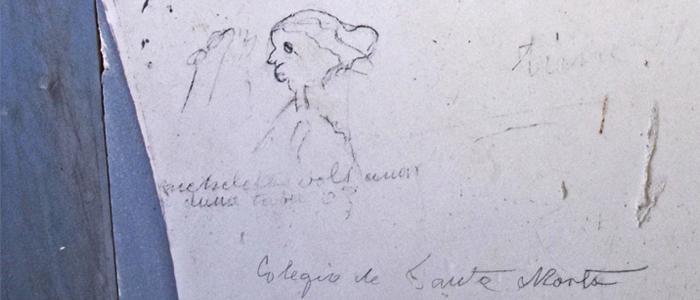

We have a rare, different kind of building with religious symbols. But, we find the key to understanding its function in a room on the first floor where the walls had a lot of graffiti, much of it in pencil, on both sides of the window overlooking Calle Archivos,. Usually, graffiti is made with a scratching implement such as a bodkin, but it is not usual that nearly all of them should be drawn with a pencil. Neither is it normal that, especially, they should consist of long lists of names, nearly all feminine. In addition, above and below these lists appears the explanation “Santa Marta School” a phrase written repeatedly everywhere.

Through Jaume Soler Soriano, we know that in the 19th century there was a “Santa Marta Academy “ in Calle Archivos that brought the teachers from Alicante Institute to examine the Baccalaureate students, but up to now we did not know exactly where it was.

Now it makes sense; the hallway (where the parents wait) with a lockable barred gate (to control access and exit of school children, particularly the boarders); the small room with the window (no doubt where the porter lived and from where he could control everything occurring in the hallway), the large kitchens (that at the time were really dining rooms for the boys and girls); the religious symbols, and that its founder, Pedro Juan Llorca, was the priest. In addition the research has developed alongside the Municipal Archive where a copy of the “Reglamento del Colegio de 2a Enseñanza Santa Marta” (Regulation of the Santa Marta Secondary Education School) is kept, and where it is shown that it was founded in 1874 and that ‘the school is proud to be Roman Catholic, Apostolic and submits happily to the Diocesan authority and its delegates’. It is therefore a school with a deep religious character.

The classroom where the graffiti was found is the girls’ classroom on the first floor; it is assumed that the boys’ classroom was on the floor below although there is no preserved graffiti. We know from the ‘Reglamento’ that there were boarders living at the school most probably on the upper floors. Curiously the students were obliged “to use the Castellano language whilst in the school” as is customary in classes of the well-off in the 19th century, but some students ignored the obligation by using Valenciano when writing on the walls.

The graffiti has been photographed in high resolution and some of it has been taken away to be preserved in Vilamuseu. The frequency with which people write and record dates on old walls is strange and this place was no exception. On the first plastering from the big renovation that converted it to a school we are given the dates 1877 and 1884, only 3 years after it opened. The most recent plastering gives us several dates from 1899 – “Rafael Ramos of Santa Marta school finished on 9 February 1899” announces one piece of graffiti. In another corner a girl drew a woman wearing glasses and her hair in a bun (a teacher?). “Esperanza Mayor and Beatriz Baldó are the best looking girls in the school and the (...) family are the ugliest...” is written elsewhere. Thus there are dozens of lines that we must now transcribe and digitally trace in order to retrieve this spontaneous testimony of our history written by several, same year students more than 140 years ago.